The Retail Investor's Blueprint for Biotech: From Lead Generation to Exit Strategy

Biotech investing looks chaotic from the outside, but retail investors can compete with PhDs by using a disciplined framework, understanding risk, and defining clear exits so they play a game of skill, not luck.

The Deceptive Simplicity of Biotech Investing

You've read the clinical trial basics. You understand that Phase 1 tests safety, Phase 2 explores efficacy, and Phase 3 confirms it works. You know about FDA pathways, orphan designations, and accelerated approval tracks. Yet somehow, knowing what happens in drug development doesn't answer the question that keeps you awake: where do I actually start as an investor?

The standard investing playbook offers no guidance here. You can't apply Warren Buffett's intrinsic value model to a company with no revenue burning $30 million annually. You can't use traditional valuation multiples. You can't rely on analyst consensus because most retail-focused platforms don't cover pre-revenue biotechs. The market is vast, chaotic, and rewards neither caution nor herd mentality.

This is the central paradox of biotech investing: the information is completely public and verifiable, yet most retail investors find themselves paralyzed by the same fundamental uncertainty that haunts institutional investors—how to systematically identify opportunities in an asset class where binary outcomes and extreme volatility are features, not bugs.

This guide offers a structured path forward, built on personal investment experience refined through both successes and costly failures. It's not a guarantee. No framework is. But it's a methodology that removes randomness from decision-making and allows you to play biotech investing as a game of skill rather than chance.

Why Non-Scientists Can Outperform PhDs in Biotech Investing

Let's address the elephant in the room immediately: I have no medical training. My background is manufacturing, technology, and sales, not biology. Yet I've consistently outperformed biotech portfolios managed by individuals with MDs or PhDs in related fields.

This isn't a boast. It's an observation about market structure that removes a psychological barrier stopping many intelligent people from biotech investing.

The core insight: biotech investing is multidisciplinary by necessity. It requires competence across science, finance, regulatory strategy, management psychology, and market dynamics. Deep expertise in one domain often creates blind spots in others.

I've watched brilliant scientists make catastrophic investment decisions because they:

- Fell in love with elegant science lacking commercial viability

- Missed management red flags because governance wasn't their domain

- Ignored cash runway problems assuming "the science will attract funding"

- Failed to recognize when competitors had already solved the problem better

- Were sometimes held back by academic prejudices about what "real" science looks like

Conversely, I've seen retail investors with no scientific training identify winners by systematically evaluating factors scientists overlook: market size, reimbursement potential, management competence, and most critically, the balance sheet.

The uncomfortable truth: having a PhD in biology is almost uncorrelated with investment success in biotech. What matters is intellectual curiosity, discipline, and a framework that forces systematic evaluation across all dimensions of risk.

All clinical data is published. It's freely available on ClinicalTrials.gov, SEC EDGAR, and company websites. The science is transparent by regulatory requirement. What separates successful biotech investors from everyone else isn't access to information—it's a methodology for organizing that information into decision rules.

Phase One: Honest Self-Assessment

Before you identify a single company, before you evaluate a pipeline or read a cash flow statement, you need to make three honest assessments about yourself.

1. What are you actually trying to achieve?

This isn't philosophical. It's tactical, and the answer completely changes how you approach every subsequent decision.

I) Short-term catalyst plays (several weeks to months): These are binary bets around specific, near-term events—Phase 2 readouts, FDA decisions, partnership announcements. You're not buying the company; you're buying volatility around a known date. Entry and exit are timed to the catalyst. Holding through it is usually a mistake unless you have a specific thesis about post-catalyst upside. Example: Buying a micro-cap before ASH conference data in early December, with a 2-week exit window.

II) Long-term core positions (2-5 years): You believe in the science, the market, and the management. You're holding through multiple catalysts, expecting volatility but not panicking. You may build a position gradually over time, averaging down when opportunities arise. You're placing a bet on commercialization or acquisition. Example: Investing in an early Phase 2 company with differentiated science in a large market, planning to hold through Phase 3 initiation, completion, and eventual approval.

III) Swing trading around trial readouts (3-6 months): You're intermediate between the above—holding 3-6 months, capturing pre-catalyst momentum and selling into strength after announcement. You're not buying the long-term thesis; you're buying the market's likely misprice of the data.

IV) Scalping or day trading post-news (hours to few days): You're capturing volatility immediately following major announcements—riding the initial emotional overreaction before rational repricing. You enter within minutes of news, hold for 2-8 hours, and exit into momentum before profit-taking arrives. This requires real-time monitoring, tight stops, and comfort with rapid reversals. Example: Data beats expectations, stock opens +40%, you buy at open, sell at +25% within 90 minutes.

Most retail investors confuse these strategies, which leads to holding periods misaligned with their theses. You can't trade a 5-year thesis like a 2-month catalyst play.

2. What is your actual risk tolerance?

Not your theoretical risk tolerance. Your actual risk tolerance—the amount of your portfolio you can allocate to biotech before your behavior changes.

Industry research shows retail investors massively overestimate risk tolerance. They believe they can handle 50% drawdowns until experiencing one, then panic-sell at the worst time.

My personal structure: I allocate maximum 10% of investable assets to biotech, then internally divide that:

- 70% to long-term core positions (2 year+ holds, higher conviction)

- 20% to catalyst/swing trades (weeks to months, tactical)

- 10% to opportunistic trades (highest risk, smallest impact)

Why this works for me: A 90% loss on the opportunistic 10% equals 0.9% total portfolio loss—survivable. The same loss on core would be catastrophic, so those positions demand higher conviction.

The key principle: Your allocation should match your actual behavior, not your theoretical comfort. Each investor should define their own allocation based on their objectives, time horizon, and emotional tolerance.

One essential rule: maintain a cash reserve. Market dislocations are buying opportunities, but only if you have dry powder.

3. Can you tolerate binary outcomes without emotional breakdown?

This is the unspoken prerequisite most investors never examine until they're experiencing it.

Biotech investments have asymmetric outcomes:

- Small wins are modest: A Phase 2 program advancing to Phase 3 might generate 20-30% upside

- Losses can be catastrophic: A Phase 3 trial failure can erase 70-90% of value in a single day

- Stagnation is common: Many companies make progress without catalysts that move the market

If you need consistent quarterly returns, emotional reinforcement from gains, or portfolio stability, biotech is not appropriate for you. You will abandon a good thesis during a drawdown because the pain of holding through volatility exceeds the theoretical upside.

Successful biotech investors must embrace long stretches of stagnation punctuated by sharp, dramatic price swings. If this type of volatility doesn't suit your temperament, acknowledge it and adjust your portfolio allocation accordingly. I consistently recommend setting up risk hedges ahead of binary catalysts—either through options strategies or by reducing position size to limit downside.

The Paradox of Risk: Late-Stage vs. Early-Stage

Investors often frame biotech strategy as "early-stage is risky, late-stage is derisked." This is partially true and dangerously misleading.

A Phase 3 company is indeed more derisked than a Phase 1 company in terms of total number of failure modes. They've proven the drug is tolerable at therapeutic doses, shows biological activity, and has preliminary clinical benefit. Fewer things can go wrong. The science has been validated across multiple steps.

But here's what most investors miss: at later stages, each remaining failure is exponentially more impactful.

Early-Stage Failure: A Phase 1 company fails to show target engagement. Stock drops 40%. The company pivots to a backup program, raises capital, and continues operating. Recovery is possible within months from a positive outcome elsewhere. The impact is single-digit percentage loss to a diversified portfolio.

Late-Stage Failure: A Phase 3 company fails its pivotal trial. The stock drops 80% in a day. The company's runway evaporates because a Phase 3 failure resets development timelines by years. Any possible recovery is 3-5 years away. The impact is 20-30% annualized loss even in a diversified portfolio.

Catastrophic Late-Stage Failure: A company reaches commercialization but faces reimbursement rejection, physician adoption failure, or unexpected safety signals. This is rare but existential. Example: A drug approved by FDA but rejected by CMS for reimbursement, making commercialization infeasible. Stock craters 90-95%.

The paradox: Late-stage biotechs have lower total risk but higher impact-per-failure. Early-stage biotechs have higher total risk but lower impact-per-failure. Neither is inherently "safer."

This changes how you evaluate risk across your portfolio. A later-stage position needs much higher conviction than an early-stage position of equivalent dollar size, because the downside is more severe when it hits.

To illustrate this risk: Kala Bio (NASDAQ: KALA) experienced a multi-bagger rally for over 3 months prior to its Phase 2b readout on September 29th, 2025. Its sole pipeline candidate, KPI-012 for persistent corneal epithelial defect, failed to meet its primary endpoint. The stock collapsed 89% following the announcement. The company discontinued the program and faced foreclosure threats from lender Oxford Finance.

Similarly, aTyr Pharma (NASDAQ: ATYR) dropped over 80% after announcing its Phase 3 EFZO-FIT trial of efzofitimod for pulmonary sarcoidosis failed to meet its primary endpoint. (I'll explain in a future article why I sold my ATYR position before the data readout—this demonstrates the importance of reading clinical trial data and spotting red flags early.)

Lead Generation: Where Do You Even Start?

You've now defined your investment objectives and honestly assessed your risk tolerance. Now comes the practical obstacle: there are roughly 500-600 publicly traded biotechs at any given time, plus thousands more in private funding rounds. If you tried to deeply analyze every single one, you'd complete zero analysis.

Where do leads actually come from?

Systematic Lead Sources

Most frameworks rank sources by institutional credibility: "Buy analyst reports first, check Reddit last." This is wrong. The quality of a lead is independent of its source. What matters is whether the lead has merit and whether you verify it.

Research-Grade Leads:

- Analyst reports from mid-tier firms (H.C. Wainwright, Oppenheimer, Jefferies): Conduct actual research with usually well-reasoned theses. Start with executive summaries, then verify core claims. Analyst reports are typically 60-70% correct on science interpretation but only 40-50% correct on valuation and timing.

- CRO and industry commentary (IQVIA): Identify therapeutic area trends, regulatory pathway changes, and reimbursement shifts.

Specialist Tools:

- BiopharmCatalyst.com: Calendar of ~6,000 active clinical trials. Filter by phase, indication, company size. Free basic version; paid tier tracks catalysts 3-6 months ahead.

- BPIQ.com: FDA catalyst calendar for 600+ micro to mid-cap biotechs covering 1,800+ drug assets. Filter by phase, indication, and mechanism. Free basic version exists; paid tier valuable for systematic tracking.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: Search trials by indication, company, or phase. Filter by "recruitment status," "results," "completion date." Compare listed timelines against press releases—discrepancies signal execution problems.

Community-Based Leads:

- r/biotechplays and r/pennystocks on Reddit: High noise ratio (5-10% good ideas), but self-filtered for people who've done basic research. I scan Reddit's r/pennystocks regularly and first encountered CGTX there. Crowd-source initial screening by reading top-voted posts, then verify independently.

- X/Twitter biotech communities: Follow institutional investors (not influencers), company accounts, key opinion leaders. Set up a list, check 2-3x weekly. Good leads surface weeks before announcements.

- StockTwits and Discord communities: Lower signal-to-noise but tighter community focus. Evaluate based on track record, not charisma.

- Substack newsletters: Quality varies wildly. Sample free issues before subscribing. Look for analysts who admit past mistakes, show their work, and challenge their own theses.

- BiostockInfo.com: Yes, this is my website, so take this recommendation with appropriate skepticism. But it exists because I was frustrated by the lack of systematic, transparent biotech analysis for retail investors. No affiliate deals, no pumping. Just detailed due diligence on companies I'm actually investing in—including ones where I got it wrong.

Your Own Discovery:

Ask "What disease area interests me? What unmet need do I see?" Then search forward by finding companies, reading their pipelines, checking trial status, evaluating financials, and assessing management. This 2-3 hour screening often reveals companies financial media hasn't yet discovered.

Using AI for Initial Screening

I use a two-prompt system depending on how I discovered the opportunity. The principle: use AI for hypothesis generation and information organization, never for final decision-making.

Quick Screener: Eliminate Obvious Duds (5 minutes)

When you first hear about a company and want to quickly check if it's worth deep research:

I'm evaluating [Company Name, Ticker] as a potential biotech investment.

Provide a preliminary assessment covering:

1. Pipeline Overview (1-2 sentences per program)

- Lead program, phase, indication

- Most advanced asset and timeline

2. Next Major Catalyst (specific date if available)

- Type of catalyst (data readout, FDA decision, etc.)

- Expected timing

3. Immediate Red Flags

- Cash runway concerns (<12 months?)

- Recent clinical failures

- Management turnover

- Listing compliance issues

4. Competitive Position (one sentence)

- First-in-class, best-in-class, or follower?

5. Quick Take: Is this worth 20 hours of deep research?

Keep total response under 400 words. Flag any uncertain information.

This eliminates ~70% of opportunities immediately. If you see recent Phase 3 failure, 4-month runway, or serial diluter management, move on.

Comprehensive Analysis: Full Seven-Pillar Review (10-20 minutes)

For companies that pass initial screening, use the detailed prompt in the Appendix: AI Prompts section at the end of this article.

Note: See end of article for exact prompts I use.

Critical caveat: AI will hallucinate data, conflate companies, provide outdated information, or misinterpret trial results. Use it to organize information and generate hypotheses, then verify every claim against:

- Company investor relations website

- SEC EDGAR filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K, prospectuses)

- ClinicalTrials.gov for exact trial status

- Company press releases (not AI summaries)

If AI says "the company completed Phase 2 in 2024," verify this is in the company's latest 8-K. If it says "the management team has successful exits," search LinkedIn for actual history.

Trust AI as a researcher's assistant, not as truth.

The 7-Pillar Framework: Systematic Due Diligence

Once you've identified a potential opportunity, you enter actual due diligence. This is where most retail investors fail—not because they lack information, but because they lack systematic process.

If you think AI research output is sufficient for investment decisions, you're making a critical mistake. Verification against primary sources is non-negotiable.

I evaluate every opportunity through seven pillars with equal weight to each (though emphasis shifts by stage and strategy). This isn't a checklist—it's a framework for asking the right questions.

Pillar 1: Pipeline & Clinical Data

What you're evaluating: What is this company building, at what stage of validation, and how differentiated is it?

Why this matters: The pipeline is the only real asset a clinical-stage biotech owns. Everything else (cash, management, partnerships) is secondary. A bad pipeline with great management still fails. A great pipeline with mediocre management can sometimes succeed.

Stage and data quality:

- What's the actual current phase of each program?

- For Phase 2 data: Did they hit their primary endpoint? (The answer is "yes" or "no"—anything else is spin.) If yes, what was the effect size and p-value? If p-value is 0.049, that's statistically significant but barely. If it's 0.01, that's robust.

- Crucially: What was the placebo response rate? High placebo response (>30%) erodes apparent efficacy. Example: If active drug shows 50% response and placebo shows 48%, the real benefit is 2 percentage points.

- Adverse event profile: Relative to placebo, what safety signals emerged?

Red flags in clinical data:

"Positive trend," "directionally consistent," "numerically superior"

→ Primary endpoint was actually missed. These phrases are corporate spin for failure.

Post-hoc subgroup analysis in press release lead

→ Original analysis failed; they cherry-picked a positive subset. If a subgroup analysis leads the headline instead of overall population results, it's a red flag.

Modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis

→ Patients excluded for "protocol deviations"—often hides adverse events or treatment failures. Standard is intent-to-treat (ITT); if they deviate, ask why.

Single-arm trial presented as efficacy proof

→ Can't prove efficacy without control group. Single-arm studies generate hypotheses only; without a placebo or active comparator arm, efficacy claims are unsupported.

Switching primary endpoints mid-trial

→ Usually means Endpoint A failed. If a company changes what they're measuring after seeing data, it's a massive red flag for opportunistic analysis.

Regulatory strategy:

- Are they pursuing accelerated approval? Fast Track? Breakthrough Therapy? Verify these designations on FDA.gov.

- For orphan indications: Is the patient population actually orphan-sized (<200,000 US patients)? Orphan status provides 7-year exclusivity, but the market is smaller.

- Has FDA previously approved drugs in this indication? If yes, what was the evidence bar? If no, higher uncertainty.

Intellectual property:

- Patent expiration dates: You want 8-10+ years of exclusivity from likely approval. If expiration is 5 years away and Phase 3 is ongoing, the window is short.

- Freedom to operate: Are there blocking patents? Can the company design around them?

- Patent portfolio quality: Filing continuation patents (strengthening) or getting weaker? Check Google Patents and WIPO.

After Pillar 1, ask:

- Is the science differentiated or "me-too" in a crowded space?

- Do clinical results justify advancement to the next phase?

- What is the regulatory path and does it have precedent?

- Is IP protection sufficient?

Pillar 2: Upcoming Catalysts

What you're evaluating: What events will drive stock movement over your holding period?

Why this matters: Catalysts are punctuation marks in biotech investing. Without them, you're holding a binary bet indefinitely. With them, you have decision points.

Near-term catalysts (0-6 months):

- What's the next expected data readout or FDA decision? Get exact date from 10-Q, not press releases (often aspirational).

- Is there an interim analysis planned? Interim data provides early go/no-go signals years before final readout.

- Partnership announcements or licensing deals imminent?

- Which conferences will this company present at? (JP Morgan in January, ASH in December, ASCO in June, etc.)

Long-term catalysts (6-24 months):

- When will Phase 2 initiate? When is Phase 3 initiation expected?

- When is BLA/NDA filing projected? (Filing itself is bullish)

- When is commercial launch expected?

Risk catalysts (negative events):

- When does cash runway expire? Companies typically fundraise 5-8 months before depletion, but if runway is <12 months and they haven't announced plans, dilution is likely.

- When is the next financing event? Check for ATM programs or shelf registrations.

- Regulatory decision dates that could go negative?

After Pillar 2, ask:

- What is the probability and timing of my next decision point?

- If I invest today, when do I have a binary catalyst to evaluate my thesis?

- Are there negative catalysts I should anticipate?

Pillar 3: Competitive Landscape

What you're evaluating: How crowded is the market? First-in-class, best-in-class, or following?

Why this matters: First-mover advantage is powerful but not guaranteed. Best-in-class is more valuable if differentiated. "Me-too" drugs in crowded markets face commercial headwinds even after approval.

Market positioning:

- First-in-class: Higher regulatory uncertainty, lower clinical bar, massive market capture upside if it works. Example: First GLP-1 for weight loss was Saxenda. Novo's Wegovy entered later and captured 90% by being better. First-in-class doesn't guarantee dominance.

- Best-in-class: Needs clear differentiation—better efficacy, fewer side effects, easier dosing, better pricing. Vague claims without numbers are red flags.

- Follower: Facing uphill battle unless genuine unmet need or true differentiation exists.

Competitive pipeline:

- Who else is pursuing the same indication? How advanced are they?

- Is the market big enough for multiple players? $10B indication can support 2-3 approved drugs. $1B indication is winner-take-most.

- What's the pricing and reimbursement environment? If comparable drugs are reimbursed at $50,000/year, that sets expectations.

Market size and commercial prospects:

- What is the addressable market (patient population × annual treatment cost)? Compare to company's peak sales projections. If they project $2B for a $15B market, that's optimistic but plausible. If they project $5B for a $3B market, that's not.

- Will reimbursement be automatic? CMS may require head-to-head trials. If your drug is 10% better but 5x more expensive, reimbursement may be restricted.

- What does physician adoption look like? Switching from existing therapy requires strong advantage. Additive is easier.

Real Example: Antibiotics Market

Issue: Iterum Therapeutics (NASDAQ: ITRM) targets uncomplicated UTIs (uUTIs) with its recently approved antibiotic but struggles to generate revenue.

Lesson: FDA approval ≠ automatic commercial success. Iterum lacks established sales, marketing, and distribution. GlaxoSmithKline (NASDAQ: GSK) approved in the same indication and brings established infrastructure that Iterum cannot match.

Outcome: Stock in constant decline, trading below $1.

After Pillar 3, ask:

- What is this company's realistic peak market share?

- Are they claiming a larger market than they'll achieve?

- Is the competitive advantage real or marketing spin?

Pillar 4: Financials & Fundamentals

What you're evaluating: Does this company have sufficient capital to reach its next catalyst? When will they run out of money?

Why this matters: Brilliant science means nothing if the company runs out of cash before proving it works. Financials are the ticking clock.

Cash position and runway:

- Current cash balance: 10-Q line item "Cash and cash equivalents"

- Gross burn rate: Total operating expenses ÷ months elapsed

- Net burn rate: Gross burn minus revenue (usually zero)

- Cash runway: Cash balance ÷ monthly burn rate = months

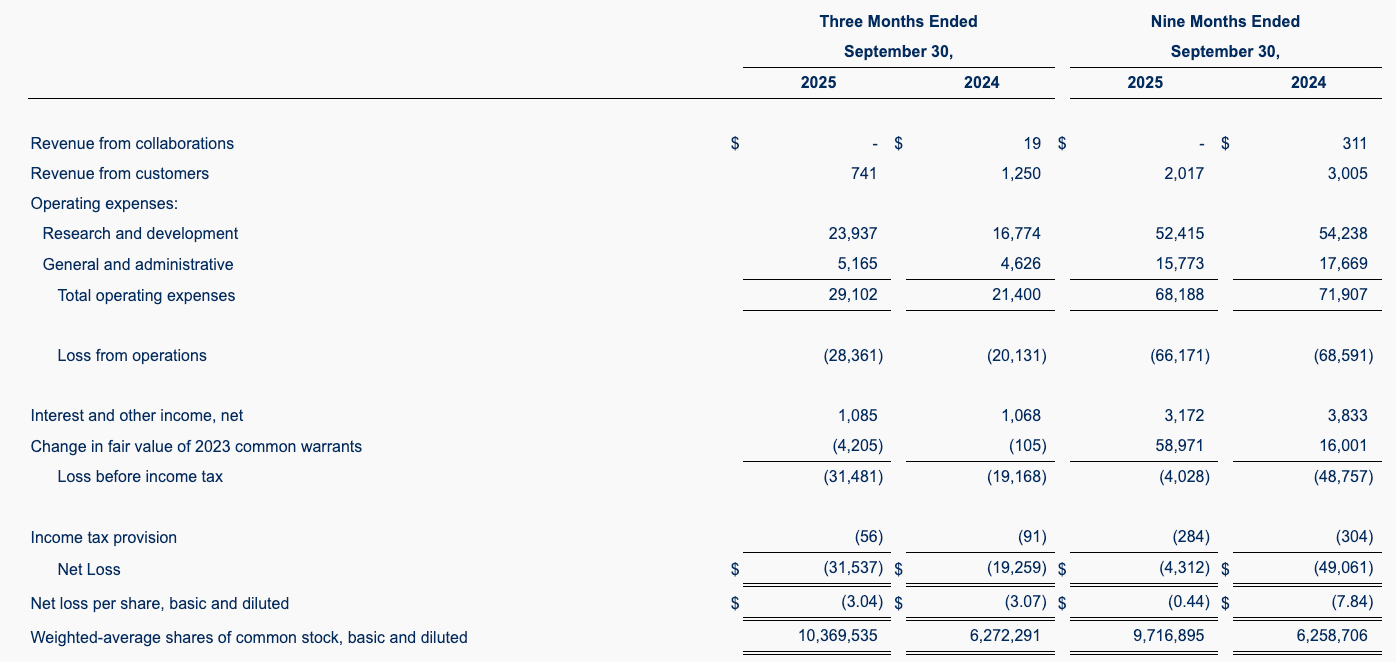

Example calculation:

- Cash: $50M

- Quarterly expenses: $20M

- Monthly burn: $20M ÷ 3 = $6.67M

- Runway: $50M ÷ $6.67M = 7.5 months

This is critically short. Companies typically fundraise when runway drops to 5-8 months, but fundraising takes 3-4 months. A 7-month runway means fundraising is imminent.

The runway trap: Most investors calculate runway and think "18 months before needing capital." Wrong. They'll need capital in 12-13 months (when runway drops to 5-8 months), not when it hits zero.

Dilution risks:

- Outstanding shares: If a company has 50M shares outstanding and needs $20-25M new capital within 12 months, that's ~15-20% dilution immediately. Over 3-5 years, dilution compounds.

- Warrant overhangs: Check 10-Q for outstanding warrants (calls on the stock). If stock is above strike prices, they'll likely exercise, diluting common shares.

- ATM programs: These allow continuous share sales at market price. If authorized at $50M with only $5M used, they can drop remaining $45M into the market at any time.

- Pre-funded warrants and PIPE structures: Some companies raise capital with complex structures. Read the prospectus carefully.

Real Example: Dilution Risk Analysis

Issue: Aligos Therapeutics (NASDAQ: ALGS) Q3 2025 earnings reveal deteriorating runway.

Financials:

- Cash Q3 2025: $99.1M (vs. $130M Jun 2025)

- Management guidance: "funding into Q3 2026"

But deeper analysis shows:

- Actual runway at $10.5M/month burn: ~8.5 months (Run dry by Q3 2026)

- Going concern warning wordings have changed to 10-Q

- Company now explicitly states "We plan to finance our cash needs"

Below quote is extract from the latest 10-Q and crossed out word is from previous 10-Q, and replaced word highlighted in yellow.

Weexpectplan to finance our cash needs through a combination of public or private equity offerings, debt financings, collaborations, strategic alliances, licensing arrangements and other marketing or distribution arrangements. In addition, we may seek additional capital to take advantage of favorable market conditions or strategic opportunities even if we believe we have sufficient funds for our current or future operating plans.

Lesson: Compare current quarter 10-Q language to prior quarter, "We expect to finance" changes to "We plan to finance," that's a red flag for imminent dilutive financing that the investors need to be aware of.

Listing compliance:

- Stock trading above $1 (NASDAQ minimum)?

- Company current with SEC filings?

- Any violations or investigations on SEC.gov?

After Pillar 4, ask:

- Can the company reach its next catalyst without dilution?

- If financing is needed, how dilutive will it be?

- Is there delisting risk?

Pillar 5: Partnership Status

What you're evaluating: What external validations exist? How dependent is the company on partners?

Why this matters: Partnerships validate science from sophisticated entities, reduce execution risk, and provide non-dilutive funding.

In-licensing (drugs acquired from others):

- What was acquired and at what cost? Expensive signals confidence; cheap signals overlooked opportunity.

- From whom? Academic lab, another biotech, or big pharma? Big pharma validation carries more weight.

- Milestone structure: Upfront-heavy or milestone-heavy? Milestone-heavy suggests licensor retained risk.

Out-licensing (rights sold to others):

- Positive signs: Geographic partnerships, indication expansion, strong upfront payments ($100M+)

- Negative signs: Core asset out-licensing for minimal upfront ($5-50M), selling everything except one program (capital crisis)

- $100M+ upfront suggests validation; $10M suggests desperation

Strategic partnerships:

- With big pharma: Valuable signal of external expert belief. Provides acquisition optionality. Read fine print—some partnerships are marketing-only.

- With CROs: Operational necessity, not validation.

- With academics: NIH grants or collaborations are non-dilutive funding. Useful but modest signal.

- Distribution partnerships: Critical for late-stage companies. Geographic exclusivity and channel partnerships de-risk commercialization.

Real Example: In/Out-Licensing Strategy

Issue: Spero Therapeutics ($SPRO) demonstrates strategic use of licensing.

In-Licensing: Spero in-licensed tebipenem pivoxil from Meiji Seika. Meiji retains Japan/certain Asian rights; Spero retains rights globally. Meiji receives low double-digit sublicensing fees capped at $7.5M.

Out-Licensing: Sept 2022—Spero out-licensed tebipenem HBr globally (except Meiji territories) to GSK for $66M upfront + $525M milestones + royalties. GSK handles Phase III, regulatory, commercialization. Spero responsible only for one Phase III trial.

Lesson: This structure is optimal—non-dilutive capital from out-licensing, de-risked execution via big pharma partner, while maintaining upside participation.

After Pillar 5, ask:

- Do external partners validate the science and strategy?

- Is the company dependent on partners for execution, or do they control their destiny?

Pillar 6: Management

What you're evaluating: Do executives have a track record of execution? Have they built or destroyed shareholder value?

Why this matters: Competent management salvages mediocre assets. Incompetent management destroys great science. Track record matters more than credentials.

Prior track record:

- CEO and CMO: Have they successfully developed and commercialized drugs? Success rate? (1 drug is luck; 3 is competence)

- Search LinkedIn for full employment history. Jumping between companies every 2 years is a bad sign. Building tenure is good.

- What happened at previous companies? Success or failure?

Relevant expertise:

- Is the CEO experienced in this therapeutic area?

- Does the CMO understand the specific mechanism? (You want domain specialists)

- Does the CFO have biotech capital raise experience?

History of shareholder treatment:

- How have they handled dilution? Raising when necessary or multiple massive offerings in short timeframes?

- Do they communicate transparently or spin bad news with vague language?

- Insider ownership: If CEO owns 0.5%, weak incentive alignment. If they own 10%+, interests align.

- Board composition: Industry veterans or random people with no background?

Red Flags:

- Executives with history of failed programs and repeated massive dilutions

- CEO and CFO lacking industry experience attempting first biotech raise

- Board that's friends/family rather than experts

- High executive turnover (suggesting internal problems)

- Executives cashing out stock while claiming confidence (huge red flag)

Real Example: Loss of Investor Confidence

Issue: SELLAS Life Sciences Group, Inc. ($SLS) carries historical baggage from predecessor Galena Biopharma.

Lesson: 2017 SEC complaint detailed a pump-and-dump scheme involving Galena (now SELLAS) where individuals manipulated stock price through paid articles, then sold at inflated prices. A proposed class action securities fraud lawsuit was dismissed in 2021, but retail investor confidence never fully returned.

Outcome: Management credibility damaged for years despite different leadership.

After Pillar 6, ask:

- Has this management team successfully executed before?

- Are their financial incentives aligned with shareholder success?

Pillar 7: SEC Filings and the Devil in Details

What you're evaluating: What is the ground truth beyond marketing spin?

Why this matters: SEC filings are legal documents filed under oath. They're the closest thing to objective truth in biotech investing. Everything else is marketing.

Recent 8-Ks (filed for significant events):

- Clinical data announced? Compare actual filing numbers to press release spin.

- Partnership announcements? Check full deal terms, not headline amounts.

- Officer departures? Unexpected exits signal problems.

10-Q and 10-K MD&A section:

- What risks does management highlight? Omissions are telling (no reimbursement discussion in commercial-stage company is suspicious).

- Accelerating burn or shifted timelines from prior quarter?

- Revenue announcements? Positive signal for commercial-stage companies.

Balance sheet and cash flow:

- Is cash falling faster than expected? Suggests hidden spending or problems.

- New debt? Some is normal; excessive is red flag.

- Does stated burn ($2M/month) match actual cash outflow? Mismatches signal accounting issues.

Insider and institutional ownership:

- What percentage do insiders own? Below 1% signals weak alignment; above 10% suggests strong conviction.

- Who owns the stock? Tier-1 VCs/hedge funds holdings suggest confidence; rotating ownership suggests doubt.

- Check Form 4 insider trades: Are executives buying or selling? Large insider sells while promoting drug progress is a red flag.

Red flags in SEC filings:

- Vague statements contradicting press releases

- Repeated timeline delays (execution problems)

- Rising expenses not matching clinical progress

- Executive compensation tied to stock price (incentivizes short-term thinking)

- Restatement of prior financials (internal control failure)

After Pillar 7, ask:

- Do SEC filings confirm or contradict the narrative?

- What are management's skin-in-the-game signals?

Applying the Framework: Why There Are No Universal Weightings

The 7 pillars are equal in principle, but here's the uncomfortable truth: I can't tell you which pillar matters most for your investment because it depends entirely on the specific opportunity and your specific thesis.

This isn't evasion. It's honesty.

The CGTX Reality Check

When I invested in Cognition Therapeutics (NASDAQ: CGTX), the framework would have screamed "red flags everywhere":

- Pipeline: Failed primary endpoint in overall population

- Clinical Data: P-values of 0.069-0.237 (well above 0.05 threshold)

- Competitive Landscape: Crowded Alzheimer's space with established players

- Delisting Risk : CGTX had NASDAQ compliance deadline (October 2025) when I made the investment decision. The risk wasn't just clinical; it was existential, but the risk actually provided an attractive entry point.

By any mechanical weighting system, CGTX was an automatic "no." Yet I invested because understanding the complete picture revealed something the surface data missed:

- The biomarker stratification showed 95% slowing in the right patient population

- The company PR after the End of Phase 2 meeting at the beginning of July showed a positive signal

- The risk/reward at that valuation made sense if you accepted the specific risks

This wasn't ignoring red flags. This was understanding them completely and determining they didn't invalidate the thesis.

The Framework Is a Lens, Not a Formula

Think of the 7 pillars as diagnostic questions, not a scorecard:

- Short-term catalyst play: You might spend 80% of your time on Pillar 2 (Catalysts) and Pillar 4 (Financials), but if you completely ignore Pillar 3 (Competition) and discover a competitor has superior data dropping the same week, you've destroyed your thesis. The "weighting" didn't save you; holistic understanding would have.

- Long-term core position: You might emphasize Pillar 1 (Pipeline) and Pillar 6 (Management), but if you overlook Pillar 7 (SEC Filings) and miss that management has been systematically diluting shareholders for years, your 5-year hold becomes a slow bleed. Again, the issue isn't weighting—it's completeness.

- Opportunistic trade: You might focus on a single catalyst from Pillar 2, but if Pillar 4 shows the company will run out of cash before the catalyst, your "opportunistic trade" becomes a dilution event. The framework catches this only if you actually check all pillars.

What Actually Matters

- Complete the framework for every investment. Don't skip pillars regardless of your strategy. The pillar you skip is usually where the thesis breaks.

- Identify the thesis-critical factors. For CGTX, it was: "Does the biomarker signal justify prospective enrichment?" Everything else was secondary to that specific thesis. For ENTA (my missed opportunity), it was: "Can I overcome my prior negative bias to objectively evaluate this new data?" I failed that test.

- Acknowledge what you don't know. Sometimes Pillar 3 (Competition) is legitimately unknowable because comparable trials haven't read out yet. Sometimes Pillar 6 (Management) is unclear because the team is new. Don't pretend certainty. Factor uncertainty into position sizing.

- Write down your thesis explicitly. Before entry: "I'm investing because [X], and I'll exit if [Y] happens." This forces you to articulate which pillars are thesis-critical and which are supporting evidence. It also creates an exit rule you can't rationalize away later.

The Brutal Truth

If you're looking for a formula that tells you "weight these pillars 60/30/10 for Strategy X," you're looking for false certainty. Biotech doesn't offer it. What the framework does offer is systematic completeness—forcing you to ask the right questions so you can make informed decisions, not lucky guesses.

The goal isn't to never make mistakes. The goal is to understand what you're getting into so that when things go wrong (and they will), you're not blindsided—you knew the risks and accepted them consciously.

That's the difference between gambling and calculated risk-taking.

That's the difference between random outcomes and improving your probability of success over time.

And that's why there are no universal weightings: every opportunity is different, and understanding that specific opportunity completely is what separates good biotech investors from everyone else. Yet here's the paradox most investors learn the hard way—rigorous due diligence gets you into the right positions, but knowing when to exit is what actually makes you money.

Exit Strategy: The Forgotten Pillar

Without an exit strategy, gains are just fantasy. Yet most investors obsess over entry and ignore exits—the actual moment they realize returns.

Types of Exits

Clinical catalyst success exit: Stock jumps 50-100%+ on positive data or regulatory approval. Sell into the pop immediately within 1-3 days. Consider re-entry after volatility cools if thesis remains intact.

Strategic acquisition exit: Big pharma or rival biotech acquires at 30-50% premium to trailing price. This is the long-term holder's exit, realizing acquisition multiples. Typical timing: 2-5 years post-investment.

Rebalancing exit: Stock appreciates 3-5x. Thesis intact but position size has grown (concentrated risk). Sell 50-75% to lock gains and reduce to manageable size. Hold remainder for upside.

Thesis change exit: Competitive landscape shifts, management departs, runway accelerates, or clinical trajectory worsens. This isn't panic—it's executing on new information.

Time-based exit: You defined a 2-year hold for a catalyst play. Catalyst hasn't materialized but hasn't failed. 2 years elapsed, opportunity cost mounts. Exit and redeploy capital.

The key principle: Set your exit conditions before entering. Each investor's objectives differ, so there's no universal rule—what matters is defining your own and sticking to it.

Discipline Rules for Exits

Discipline 1: Pre-define exit conditions before entering

- "I will exit if Phase 2 misses primary endpoint"

- "I will sell 50% if stock reaches 3x from entry"

- "I will hold max 3 years regardless of thesis status"

When the catalyst hits, execute the plan, not reconsider it.

Discipline 2: Sell into strength, not weakness

- Stock jumps 50% on positive data? Sell 50% of position.

- Stock drops 30% on market selloff? Hold or add (if thesis unchanged).

Discipline 3: Don't get attached to positions

I've held winners for 5 years and losers for 6 months. Duration is irrelevant. What matters is thesis alignment. If thesis breaks, exit immediately regardless of sunk cost psychology.

Discipline 4: Don't let tax considerations override investment logic

Tax advantages matter, but not more than protecting profits. If your optimal exit is at month 4 but you're 2 months from favorable tax treatment, exit anyway. Holding a 200% winner hoping to avoid taxes, only to watch it collapse 50%, is false economy. Know your jurisdiction's thresholds, then make investment decisions first—tax optimization second.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Confusing Correlation with Causation in Partnerships

The error: Partnership announcement → stock jumps 30% → "partnership validates science"

Why it's wrong: Partnership validity ranges from cosmetic (marketing-only, minimal financial commitment) to strategically meaningful (co-development with pharma funding).

How to avoid it:

- Read the actual partnership agreement in the 8-K filing

- Check milestone structure: $50M+ upfront & $500M+ milestones = real validation; $1M upfront = cosmetic

- Big pharma partnerships are bullish; small CRO partnerships are operational necessity

Mistake 2: Not Adjusting for Biomarker Dependency

The error: Phase 2 efficacy in biomarker-selected population = Phase 3 will confirm in unselected population

Why it's wrong: Efficacy narrows dramatically. Top 30% biomarker-selected patients at 60% efficacy → overall population at 35% efficacy.

How to avoid it:

- Always check if Phase 2 was prespecified biomarker analysis or post-hoc discovery

- Post-hoc discovery = 50%+ Phase 3 failure probability

- Prespecified = 30-40% Phase 3 failure probability

- If Phase 3 broadens from biomarker-selected to unselected, expect 20-40% efficacy dilution

Mistake 3: Underestimating How Quickly Runway Expires

The error: "24-month cash runway" = 24 months until crisis

Why it's wrong: Companies fundraise 5-8 months before runway depletion (fundraising takes 3-4 months). "24-month runway" = "15-16 month cash before financing pressure"

How to avoid it:

- Always subtract 8 months from stated runway as buffer for fundraising

- Calculate personally: Cash ÷ monthly burn = months. If <18 months, financing likely within 12 months

- Monitor cash balance and burn rate trends quarterly

- Check for ATM programs or shelf registrations (signal financing already planned)

Mistake 4: Focusing on P-Values Instead of Effect Sizes

The error: "Phase 2 met primary endpoint, p=0.02" = efficacy proven

Why it's wrong: Statistical significance ≠ clinical significance. 5% improvement over placebo is statistically significant (with large enough sample) but clinically irrelevant.

How to avoid it:

- Always find the effect size, not just p-value

- Compare active vs. placebo arms: "Active 55%, placebo 50%" = 5 percentage point absolute benefit (small)

- Compare to competitors: If competitor shows 40% efficacy and new drug shows 42%, differentiation is marginal

- Ask: "Would I prescribe this if I were a physician?" If your answer is 'no, I'd use the competitor instead,' that's a signal efficacy is inadequate for differentiation

Mistake 5: Assuming Revenue Scales Linearly

The error: $50M year 1 → extrapolate to $200M by year 4

Why it's wrong: Commercial execution varies wildly. Many approved drugs plateau well below peak sales estimates due to physician adoption, reimbursement penetration, competitive response.

How to avoid it:

- Don't project peak sales beyond 5 years post-approval

- For commercially launched drugs, compare actual trajectory to management guidance. If actual < guidance, reimbursement or competitive headwinds are materializing

- Compare to similar drugs in same indication for real comps

Your First 2 Weeks: From Theory to Action

If you're ready to move from theory to action:

Week 1: Identify Lead & Quick Screening

- Source: One of the channels mentioned (analyst report, Reddit, BiopharmCatalyst, etc.)

- Time investment: 1-2 hours to preliminary research

- Outcome: Find 3-5 interesting companies (not investments yet)

- Action: Run First-Pass Screener AI prompt on your companies

- Time investment: 30 minutes per company

- Outcome: Determine which company is worth deeper AI research

- Next Action : Run Comprehensive Due Diligence Prompt

- Time investment: 1-2 hours per company

- Outcome: Determine which company is worth Deep Due Diligence

Weeks 2+: Deep Due Diligence

- Action: Complete 7-pillar analysis on chosen company

- Research: Read 10-Q/10-K, clinical data, SEC filings, competitive landscape

- Time investment: 15-20 hours minimum

- Outcome: Understand if this company merits investment

Decision Point

- Make a note: Pre-entry thesis (what do you believe?) and exit conditions (when will you sell?)

- Execute: Enter with defined size based on your risk tolerance and strategy

- Time investment: 2-3 hours

Ongoing (Regularly)

- Monitor: Catalysts, financials, thesis changes, and social media platforms like Stocktwits, LinkedIn, and X often provide minor updates that may not be considered PR-worthy. However, these updates can occasionally offer valuable insights.

- Time investment: 5-10 hours/month per position

- Outcome: Stay updated without obsessive watching

Important Caveat

Everyone's timeline is different. Sometimes I spend over a month before investing; sometimes I open a small position first and conduct in-depth research. However, I never skip any step of the framework. I apply this framework non-negotiably. The only exception: pure scalping plays (hold <24 hours)

Conclusion: From Framework to Edge

The more sophisticated valuation models—risk-adjusted net present value (rNPV), enterprise value to R&D expense ratios, and countless others—promise precision but often deliver disappointment. If these quantitative approaches worked flawlessly, institutional investors would not have suffered massive losses from recent collapses like MLTX, QURE, and BHVN. This reality exposes a fundamental truth: no formula can substitute for disciplined analysis and emotional restraint.

Rather than pursuing mathematical elegance, this framework prioritizes what actually works: systematic thinking that any investor can understand and execute. Complex models create false confidence; simplicity creates accountability.

What My Framework Can Offer

- A systematic method for self-assessment

- A process for sourcing opportunities

- A seven-pillar due diligence structure

- Real portfolio examples that demonstrate framework application in practice

- Exit strategy discipline

- Common mistakes to avoid

The ultimate goal is profit. Noble causes like supporting innovation exist, but financial returns drive behavior. With systematic analysis, clear risk management, and emotional discipline, retail investors can compete effectively in biotech without insider access or advanced degrees.

Time is Our Advantage

The biotech market operates continuously—next week, next month, next year. This permanence transforms patience from a liability into a strategic advantage.

The Path Forward

Begin with a single position. Execute your framework methodically. Observe the results. Refine your approach. Over time, this disciplined iteration builds genuine edge—the kind that compounds and sustains.

Framework-based investing levels the playing field. Move deliberately. The market will reward consistency.

Appendix: AI Prompts I Actually Use

See sections "Using AI for Initial Screening" above for more detail.

Quick Screener Prompt

I'm evaluating [Company Name, Ticker] as a potential biotech investment.

Provide a preliminary assessment covering:

1. Pipeline Overview (1-2 sentences per program)

- Lead program, phase, indication

- Most advanced asset and timeline

2. Next Major Catalyst (specific date if available)

- Type of catalyst (data readout, FDA decision, etc.)

- Expected timing

3. Immediate Red Flags

- Cash runway concerns (<12 months?)

- Recent clinical failures

- Management turnover

- Listing compliance issues

4. Competitive Position (one sentence)

- First-in-class, best-in-class, or follower?

5. Quick Take: Is this worth 20 hours of deep research?

Keep total response under 400 words. Flag any uncertain information.

Comprehensive Due Diligence Prompt

For companies that pass initial screening, use this detailed prompt:

(Use your AI's most advanced analytical mode for best results)

I'm evaluating [Company Name, Ticker: XXX] as a potential biotech investment.

Provide a comprehensive analysis covering all key investment dimensions based on data without bias nor prejudice:

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 1: PIPELINE & CLINICAL DATA

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

1. Complete Pipeline Inventory

For EACH program, provide:

- Drug name/code, mechanism of action (plain English)

- Indication and target patient population

- Current development phase

- NCT trial identifier (if available)

- Latest clinical data or trial status

- Primary endpoint results (if data released): p-value, effect size, placebo response rate

- Any safety concerns or adverse events

2. Lead Program Analysis

- Which is the most advanced/valuable program?

- Did most recent trial meet its primary endpoint? (yes/no, not spin)

- Quality of data: robust or marginal?

- Any red flags in data presentation? (post-hoc analysis, endpoint

changes, vague language)

3. Regulatory Strategy

- FDA designations: Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Orphan Drug?

- Regulatory pathway and precedent in this indication

- Patent expiration dates (if disclosed)

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 2: UPCOMING CATALYSTS

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

4. Catalyst Timeline

- Next major catalyst: type and specific expected date

- All significant events next 12-18 months

- Are these dates from SEC filings or company guidance?

- Any history of timeline delays?

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 3: COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

5. Market Positioning

- First-in-class, best-in-class, or follower?

- Top 3-5 competitors in lead indication

- How they compare: mechanism, phase, timeline, data quality

- Competitive differentiation (real or claimed)

6. Commercial Potential

- Market size (patient population × annual treatment cost)

- Company's peak sales projections vs. realistic market analysis

- Pricing environment and reimbursement precedent

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 4: FINANCIALS & FUNDAMENTALS

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

7. Cash Position & Runway

- Latest cash balance (which quarter?)

- Average monthly burn rate (calculate from recent quarters)

- Cash runway in months

- When will they likely need to raise capital?

8. Dilution Analysis

- Current shares outstanding

- Recent financing (last 12 months): amounts, terms

- Outstanding warrants, options, registered shares

- Total potential dilution percentage

- Any ATM programs and remaining capacity?

9. Financial Red Flags

- Debt or convertible notes with concerning terms?

- Burn rate accelerating?

- Any going concern warnings or listing compliance issues?

- Stock trading above $1 (NASDAQ minimum)?

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 5: PARTNERSHIP STATUS

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

10. Strategic Relationships

- Any big pharma partnerships or licensing deals?

- Deal terms: upfront payment, milestones, royalties

- Is this validation or desperation?

- Does company control its destiny or depend on partners?

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 6: MANAGEMENT

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

11. Leadership Assessment

- CEO: background, prior companies, track record

- CMO: relevant therapeutic expertise, drug development success rate

- Insider ownership levels

- Recent executive departures?

- Any history of shareholder-destructive decisions at prior companies?

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

PILLAR 7: SEC FILINGS & RECENT UPDATES

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

12. Recent Filings & News

- Latest significant 8-K filings (last 6 months)

- Any discrepancies between press releases and SEC filings?

- Timeline changes buried in 10-Q that weren't in press releases?

- Recent clinical trial registry updates

13. Insider & Institutional Ownership

- Insider ownership percentage?

- Who owns the stock?

- Form 4 insider trades (last 12 months):

* Are executives buying or selling?

* Large sells during clinical progress = red flag

* Recent insider purchases at low prices = conviction signal

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

SYNTHESIS

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

14. Investment Assessment

- Deal-breakers: Recent clinical trial failure? Cash crisis?

Management red flags? Delisting risk?

- Bull case (3-4 sentences)

- Bear case (3-4 sentences)

- Primary risks that could destroy investment thesis

- Is this worth 15-20 hours of detailed verification? Why or why not?

═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════

IMPORTANT: Flag any information you're uncertain about. Note data sources

where possible. Highlight any contradictions between company narrative and

actual data.

Workflow

For random social media mentions:

- Run First-Pass Screener (5 min)

- If no red flags → Run Comprehensive Prompt (10 min)

- If still promising → Begin 15-20 hour verification process, sometimes whole process may take more than a week

For high-quality leads (analyst reports, elite fund holdings):

- Skip straight to Comprehensive Prompt

- Begin systematic verification immediately

Critical reminder: AI will hallucinate, conflate companies, provide outdated information, or misinterpret results. Verify every claim against primary sources before making any investment decision.